We think there are ways to design interfaces with the flows of electronic data that run through our cities so that they can be experienced as an enriching complement to other, more material phenomena. Edge Town is a design-led research project to test this hypothesis; a proposal of not just how to live, but how to live well in urban environments which have an ever-increasing and complex electronic component.

From our many orbits of London, driving in and out of the city limits, we have become enthusiastic connoisseurs of the landscapes created where open country rubs up against pockets of suburbia and the city’s transport networks. In terms of scale, texture and animation, these places are unique. They contain unregulated tracts of land, put to eclectic use, which present intriguing vistas full of brutal thresholds. And although these are lonely places, removed from the city proper, they are populated (albeit transiently) by the thousands of people who daily speed through them in their vehicles. But what happens if you leave your vehicle? Outside our car – unshielded, un-power-assisted – exploring hard shoulders, climbing motorway embankments, standing under flight paths, we found ourselves exhilarated. It’s thrilling to be so out of scale with the massive shapes and high velocities of these frontier environments, to feel free of the city and yet reconnected to it in a way that is raw, visceral.

The turbulent, wreckage-strewn perimeter of the city demarcates more than just its physical edges. It also represents a transition in the landscape’s invisible characteristics: a change in its air chemistry, its temperature, and the density of its electromagnetic space of media channels and data networks. Approaching London, a dormant car radio will crackle into life as the city’s radio stations come within range – the pop and hiss of the patchy radio ‘landscape’ analogous to the fragmented texture of the visual landscape beyond the windscreen.

Spread along London’s frontier belt is Edge Town, a sprawling borough of angular structures, many of them inhabited, and machines which sample the tidal flows peculiar to this city-limit environment.

Arrays of electronic sensing devices, called ‘noise farmers’, litter the region, clustered around the best vantage points. Noise farmers record the textures and animation of this transitional landscape: micro-landscapes of dust and static, patterns of merging traffic and circling aircraft, flows of pollutants, frequencies of flickering pixels and cell-phone signals. The streams of data generated by these sensors are channelled over electronically irrigated tracts of land, intermingling and thus becoming ever more abstract as they flow from sensor to transmitter to sensor, in vast intermixing daisy chains of devices. Signage provides information about each ‘data climate’, indicating the qualities of the terrain in terms of data flow – for example, whether it’s quiet or turbulent, dormant, unstable, rhythmic.

Edge Town’s electro-physical topography affords many different kinds of ownership and inhabitation, from ‘data allotments’ (patches of land visited occasionally to sample certain aspects of the city) to permanent townhouses with gardens. Edge Town living requires housing with high levels of security and noise-proofing, but this necessity is offset by the noise farmers, which translate sections of Edge Town’s road networks and flight paths into fantastic sensorial extensions of the house and garden. Life in Edge Town is not a nightmare of sensory deprivation, but neither is it a nightmare of information overload. Edge Town is a place of enlivening, provocative vistas and cosy domestic shelters – a hilltop vantage point from which to experience the multiplex energy of the city.

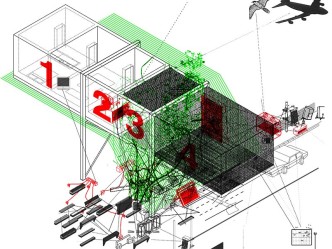

A typical Edge Town house is a modular structure of concrete, steel mesh and soundproofing materials, and is built over a busy trunk road at a city-limit location. This elongated form consists of a series of chambers. At one end of the house is the main living area, a bunker-like space (chamber 1) protected from its harsh environment by thick concrete walls, soundproofing and air conditioning. At the other end of the house, a steel-mesh cage provides an exposed chamber above the busy carriageway (chamber 4). Sandwiched between these contrasting spaces, the sheltered and the exposed, are two partially enclosed chambers (chambers 2 and 3) – yard-like spaces which have some noise-shielding in their walls but are open to the sky.

The orientation of the house perpendicular to the road, and the various degrees of its shielding, ensure that each compartment promotes a different kind of relationship – or interface – between the internal, private ‘home space’ of the house and its extreme environment. The air garden, a place totally exposed to weather and noise and exhaust fumes, is no domestic retreat, but it is perfect for watching the streaming lights of cars at night, or perhaps the burning wreckage of a crash at dusk. The transitional, semi-exposed chambers in the middle of the house provide quieter, wind-shielded vantage points with good views – up, of sky and cloud and aeroplane vapour trails; down, through the mesh flooring, of the embankment and the blurred sweep of traffic.

A closer inspection of the roadside environment – where the tarmac stops and the grass embankment begins – reveals a wild and fascinating landscape, full of the detritus of city commuters, and rich in plant and animal life thriving in the nitrogenous air. These stormy, secret gardens, constantly bombarded by material from the roadway, offer a wide variety of textures for those willing to look: patterns of dust and dirt, geometric fragments of glass and plastic, the exotic shapes of burnt-out tires, intertwining vortices of litter and dead plant matter.

Just as householders tend their gardens to improve the outlook, residents of Edge Town can adjust the position of electronic sensing machines to better capture the ethereal turbulence of these roadside ecosystems. Physically austere, but with points of vulnerability (the sensors), these machines sample flows of roadside materials – the rate of dirt build-up, the shapes of pieces of dust, the rhythm of passing cars – and then transmit these samples in data streams, or display them in light patterns. In a well-tended ‘garden’ these transmissions are received by noise broadcasters, machines which re-transform these pieces of electronic data into images, sounds and shapes of different resolutions.

The clustering of noise farming and broadcasting machines creates an electronic ecosystem of interactive objects. Chain reactions of activity occur. As one device activates, it triggers – or pollinates – the next. And so on. Complex patterns of image and noise emerge from rhythms and bursts of sound, movement, heat and light. Within each electronic ecosystem, certain devices are usually fixed in one place to sample a particular data flow – the frequency of passing cars, for example. Other devices are regularly moved around so as to isolate, translate or amplify a less consistent feature of the roadside environment. Tuned and tended like garden allotments, each ecosystem has a unique behaviour which reflects how it is maintained. Typically, the plants on the embankment grow up through the floor of the house’s yard space, interacting with the sensors and electromechanical foliage of the noise machines, the synthetic influencing the organic and vice versa.

The arrangement of simple building materials in the house’s structure, combined with the electronic ecosystem of noise-farming and broadcasting devices, integrates – rather than isolates – the house with its dramatic roadside site, from outside and inside. Within, a complex range of experiences is available. The air garden above the carriageway and the bunker-core offer experiences at opposite extremes, but between them lies a subtly nuanced domestic landscape where the occupier can enjoy selected and transmuted aspects of the outside world – and, importantly, can influence this aesthetic integration.

Where do Edge Town residents go for recreation? If Edge Town has a cultural centre – a ‘downtown’ where its mishmash geography is at its most concentrated – then it is the environs of the airport. A stroll from the tube station to Heathrow’s perimeter fence, through a car park and a field of allotments, confirms the extent to which normal rules do not apply here. Cattle graze nonchalantly among spectacular rigs of aviation electronics and shimmering landing lights; an overgrown footpath next to a park ends abruptly at a flashing sign warning of ‘aircraft crossing’ – and all this as jet plane after jet plane roars overhead. Or … silence. Every few hours, Heathrow's traffic controllers switch the runways used for landing and take off, compounding the hectic drama of the landscape. All at once, a place of deafening noise goes eerily calm – or the calm suddenly explodes.

Situated in this tumultuous landscape, directly underneath the airport’s final approach flight paths, are ‘sensor parks’, fenced-off patches of land containing monitoring and display systems which respond to the electro-physical flux of their environment. These systems sense and display information about each plane as it approaches, passes overhead and lands, and also connect with centralised airport systems to find other information about the plane.

The structure of the sensor park provides support for a host of screen-based and electromechanical displays, which offer numerical representations of the data collected from the sensors. Planes are ranked according to various sets of characteristics, creating league tables of an unusual kind. Noisiness (sound level) is compared with shininess (the amount of light the body of a plane reflects), glide slope wobble (the smoothness of the plane’s decent) with passenger ‘eclecticity’ (the eclectic ethnicity of the passenger list), and so on. These league tables are shown beside the latest data to arrive at the sensor park, providing a rapidly changing reference chart of thought-provoking comparisons.

From the perspective of the viewer at the perimeter fence, the read-outs on the elevated display units are superimposed on the scene of the landing planes. It’s like watching sport on television when race times, speed or world record information is flashed up over the live video signal, fusing the physical event and its informational indices in one concentrated info-vista of noise and numbers.